In this blog, Hettie Moorcroft, Sam Hampton & Lorraine Whitmarsh from the University of Bath discuss misconceptions around concern about climate change, income level, and ability to take action.

There is growing evidence that social and economic transformation is required to limit the worst impacts of climate change. While there exists a common misconception that only the wealthy are willing and able to take action, in this blog, we draw on nationally representative surveys on public attitudes and behaviours to demonstrate the widespread nature of climate concern. We then explore climate actions that can be taken on any budget, concluding that climate action can be accessible to all.

Concern about climate change is widespread

Concern about climate change is high throughout the world. In a survey of 20 different populations across Europe, Russia, the Americas and the Asia-Pacific region, the Pew Research Centre found that a median of 57% consider climate change to be a ‘very serious problem’, and 58% think that their governments are doing too little to reduce its effects.[1] Public attitudes do vary by country, but there is mixed evidence for the link between wealth and worry. The Pew study found higher levels of concern amongst developed than developing countries. However, in another comparative survey of Brazil, Sweden, the UK and China, support for strong climate policy was highest in Brazil.[2]

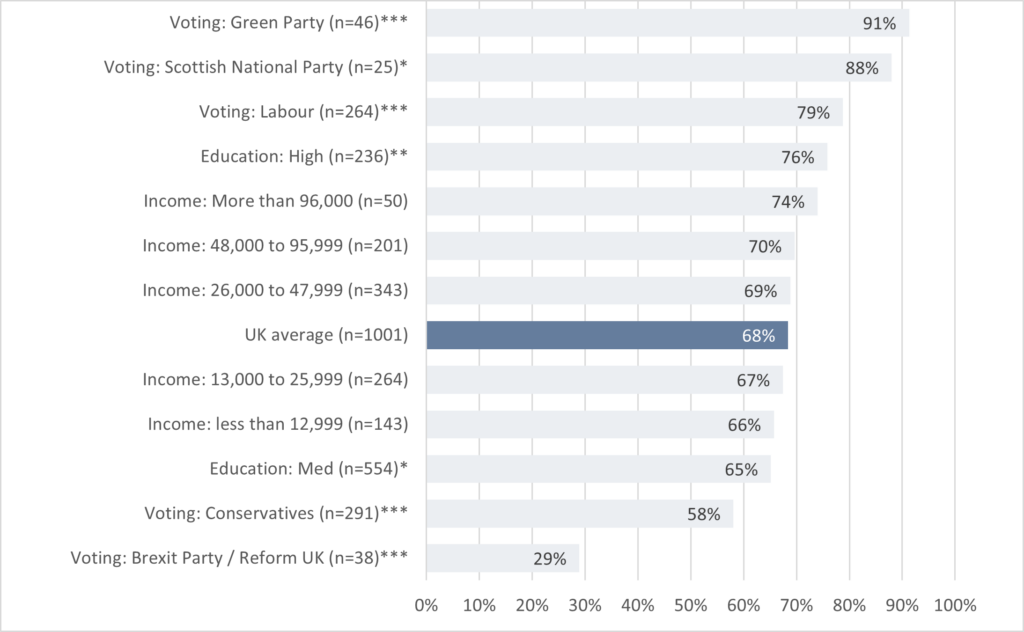

In our own unpublished research on the UK, we asked respondents how urgently they thought climate change needed to be addressed.[3] As shown in Figure 1, higher income groups show higher levels of concern, but not to a statistically significant extent. Political affiliation and education are more significant predictors of perceived urgency.

Small, low cost actions make a difference

Globally, switching to low carbon technologies such as electric vehicles and heat pumps which enable individuals to reduce their personal carbon emissions may not be currently as accessible to lower-income groups[4] and public transport may be unaffordable to many, and sometimes unavailable to the poorest neighbourhoods in cities.[5]

However, there are a range of actions that individuals wanting to tackle climate change can take, regardless of income level. In fact, many of the most effective options don’t cost anything to implement, and often incur cost savings.[6]

In the transport and food domains, these include living car free and cutting back on flying, as well as reducing meat consumption and food waste In the energy domain, although the installation of relatively expensive heat pumps, rooftop solar panels and renewable heating systems are estimated to have the greatest mitigation potential on a global basis,[7] in many countries there remains significant potential for emissions reductions through lower-cost measures such as reducing thermostat temperatures or installing thermal insulation.[8]

In fact, cost saving potential of these interventions might explain the greater uptake by lower income households found in our survey (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Proportion of people in each income decile who say they ‘make a great deal of effort to save energy’

Your voice matters

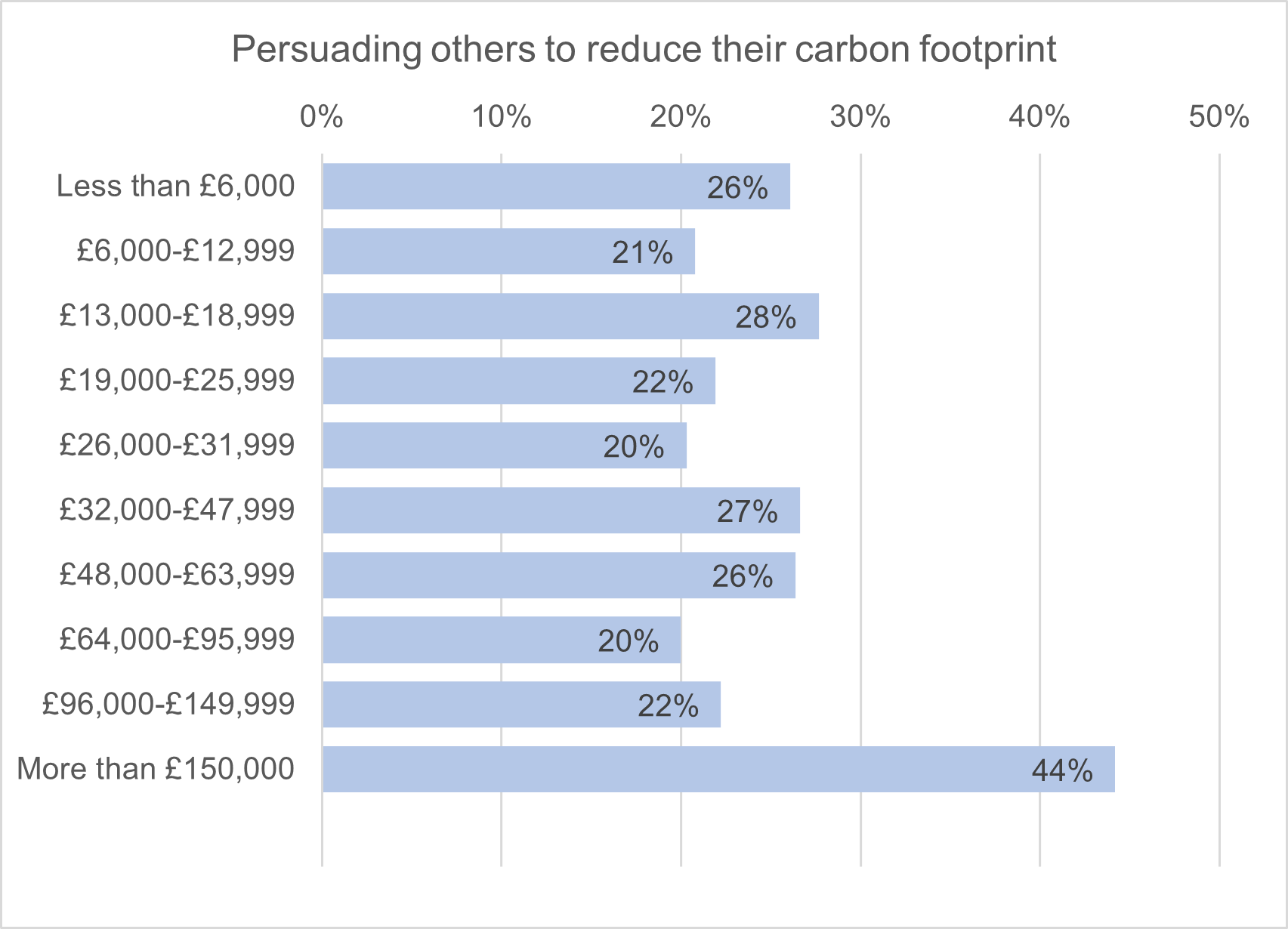

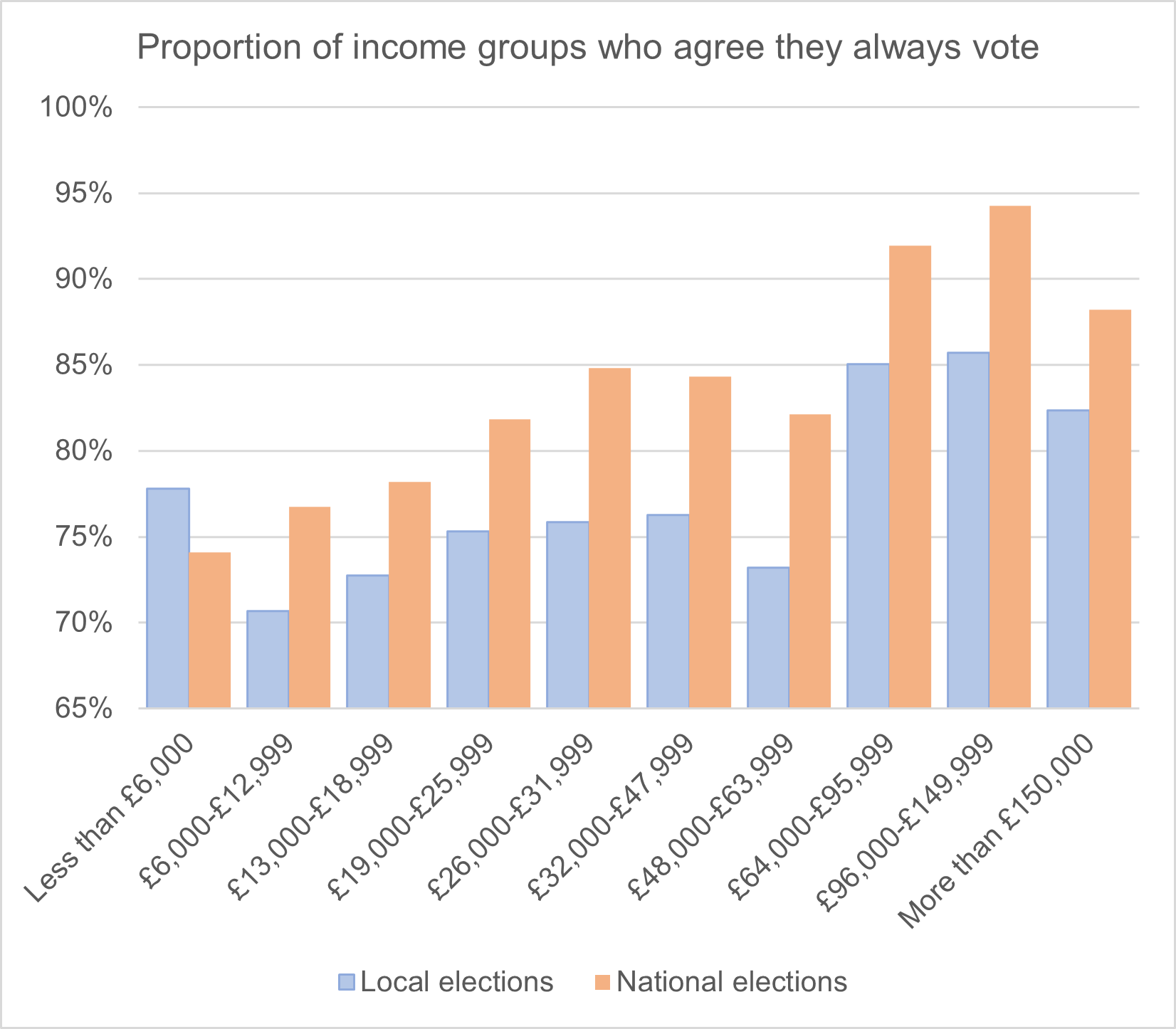

Reducing personal carbon emissions is not the only way to take climate action.[9] Influencing others, either through personal and professional networks, or through public-sphere activities such as voting or political activism are key ways in which individuals can seek to alter systems of provision. Although higher earners are currently the most likely to exert their influence on social networks (Figure 3), and to vote in local and national elections (Figure 4), there is clear opportunity for people of all income levels to use their voice to take action on climate.

Figure 3 – Proportion of people in each income decile who actively persuade friends, family and colleagues to reduce their carbon footprints

Figure 4 – Proportion of people in each income decile who agree with the statement ‘I always vote in local / national elections’

Conclusion

With the level of public concern for climate change high across income groups, it is important to highlight that there are widespread opportunities for individuals to contribute to climate action, regardless of wealth.

However, those who contribute the most to greenhouse gas emissions are also least likely to feel its impacts. There is a clear imperative for the wealthiest people in society to take most responsibility for reducing their emissions, and governments must act to ensure that the costs are borne by those with the largest wallets.

References

[1] Funk, C., Tyson, A., Kennedy, B., Johnson, C., 2020. Science and scientists held in high esteem across global publics. Pew research center 29.

[2] CAST, 2021. Public perceptions of climate change and policy action in the UK, China, Sweden and Brazil. (CAST Briefing 10). Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations.

[3] Hampton, S., Whitmarsh, L., 2024. [PREPRINT] Carbon Capability Revisited: Theoretical Developments and Empirical Evidence. Available at SSRN 4569479.

[4] Sovacool, B.K., Lipson, M.M., Chard, R., 2019. Temporality, vulnerability, and energy justice in household low carbon innovations. Energy Policy 128, 495–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.01.010;

Mohammadpourkarbasi, H., Sharples, S., 2022. Appraising the life cycle costs of heating alternatives for an affordable low carbon retirement development. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 49, 101693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101693.

[5] Valenzuela-Levi, N., 2023. Income inequality and rule-systems within public transport: A study of Medellín (Colombia) and Santiago (Chile). Journal of Transport Geography 112, 103700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2023.103700.

[6] Valenzuela-Levi, N., 2023. Income inequality and rule-systems within public transport: A study of Medellín (Colombia) and Santiago (Chile). Journal of Transport Geography 112, 103700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2023.103700.

[7] Ivanova, D., Barrett, J., Wiedenhofer, D., Macura, B., Callaghan, M., Creutzig, F., 2020. Quantifying the potential for climate change mitigation of consumption options. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 093001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab8589.

[8] IEA, 2022. Energy Efficiency 2022. Paris, France.

[9] Hampton, S., Whitmarsh, L., 2023. Choices for climate action: A review of the multiple roles individuals play. One Earth 6, 1157–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.08.006.