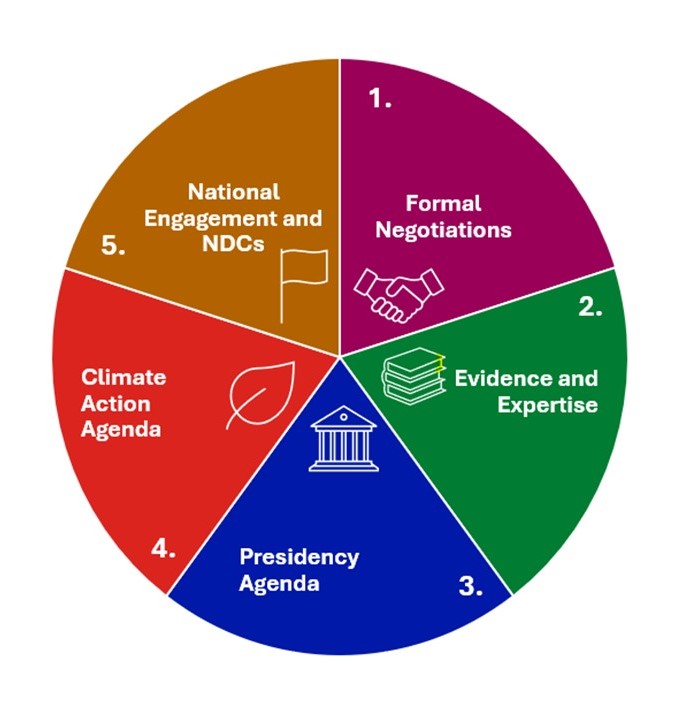

In this blog, Steve Davison (University of Cambridge) and Dr Kristy Faccer (University of Toronto) outline five tracks for engagement and impact around COP for higher education representatives.

Credit: Steve Davison

This month, 50,000 people are expected to descend on Belém, Brazil, for the annual UNFCCC Climate Summit and Conference of the Parties – or COP, as it’s commonly known. Around half of these are government affiliated delegates and around 10,000 are known as observers, including an estimated 3,000–4,000 from higher education institutions (HEIs) around the world.

At the heart of COP are the negotiations between state governments on the details and progress of international climate policy. So this begs the question, where do university and college representatives fit in? What are they hoping to achieve by going?

Usually, HEI representatives and academics attending are seeking to influence the conversation around climate action in some way. But, this isn’t your typical academic conference. In this blog post, we attempt to break down the different types of HEI engagement around COP to create a kind of taxonomy of HEI influence. This is not a definitive account, but a tool to help readers make sense of a complex landscape and higher education representatives focus their energy and strategies for engagement.

First a brief clarification: while this piece focuses on HEIs, their influence is channelled through the representatives it supports and enables. Our starting point, therefore, is to view universities (or colleges/HEIs) as actors in their own right – while recognising that individual academics, when empowered and supported, can also act as extensions of institutional influence and value addition.

1. Formal Negotiations

The first and most visible track of engagement is the formal negotiations – the core function of the Conference of the Parties and the part most people associate with it. So what’s being negotiated? Collective action to address climate change – efforts to “stabilise greenhouse gas concentrations” (UNFCCC, 1992) and to “hold the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels,” while pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C (Paris Agreement, 2015).

More specifically, negotiations are about what governments commit to do: setting and strengthening targets to reduce emissions, developing adaptation plans and strategies, providing finance, supporting technology development, and building capacity to achieve these goals. These commitments take the form of formal decisions. While not legally enforceable, they are politically binding and central to the global climate regime.

In recent years, the focus has shifted from target-setting to implementation – particularly how these commitments are reflected in the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which sit at the heart of the Paris Agreement and drive national reporting and action.

With 197 Parties to the UNFCCC, the negotiation process is a vast and highly organised operation. Much of the detailed work takes place ahead of the COP, divided into thematic work programmes and subsidiary bodies. One relevant programme of work from among the many themes and component parts of the agreements is called Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE). ACE covers Article 6 of the UNFCCC and Article 12 of the Paris Agreement and focuses on education, training, public awareness, and participation. For this reason, it is particularly relevant to higher education institutions. It is also the focus of increasing activity among university representatives at COP and annual Subsidiary Body meetings in Bonn.

As mentioned above, HEI representatives attend negotiations as observers. This means they can access or observe dialogue on key issues but cannot directly intervene in negotiations. Academics can also be included in national delegations to provide expert advice and input on particular topics or technical areas of the negotiations in service of the government.

That said, direct participation isn’t the only route to influence. A great deal of informal engagement happens “in the wings” – through meetings with delegations, advice on specific positions, decisions, or submissions made via the observer constituencies. This type of advisory also happens in the lead up to COP events and throughout the year, leading to impactful relationships and interactions between HEI and government representatives.

Tracy Bach and Beth Martin have written an excellent paper for researchers and students on navigating global environmental conferences, which provides a more detailed overview of the structures, processes and academic engagement opportunities associated with the negotiations.

RINGO COP interventions. Photo credit: Dr Kristy Faccer

2. Evidence and Expertise

The second track centres on knowledge and evidence. Universities play a critical role in supporting the UNFCCC process through the provision of independent research, analysis, and expertise. This is arguably the contribution most closely associated with higher education, and where universities have achieved their greatest and most consistent impact. In spite of recent questions regarding whether this model remains as effective today, facilitating the science–policy interface lies at the heart of the university mission and is a defining strength of the sector.

The UNFCCC itself is science-based by design. From its inception, it has institutionalised evidence as a core pillar of its functioning. Article 4 of the Convention commits Parties to “promote and cooperate in scientific, technological, technical, socio-economic and other research” and to “exchange scientific, technological, socio-economic and legal information.” The Paris Agreement reinforces this principle, affirming that “an effective and progressive response to the urgent threat of climate change” should be grounded in “the best available scientific knowledge.”

Several formal mechanisms embed the science–policy connection to the global climate agenda and policy negotiations. Chief among them is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) established in 1988 and has informed the formal United Nations framework agreement from its inception in 1992. The Convention recognises the IPCC as the authoritative source of climate science through its assessment and other reports. Report findings are received and discussed by the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), which communicates scientific input to the COP. Parties, through the SBSTA, can also commission specific technical or scientific reports through the IPCC.

For academics, contributing to the IPCC – whether as an author, reviewer, or expert contributor – is one of the most direct ways to feed research into the UNFCCC system. But beyond the IPCC, there are a range of formal dialogue mechanisms designed to connect scientists and policymakers. These include the Structured Expert Dialogues (SEDs), which bring researchers and negotiators together for moderated exchanges, and the Research Dialogues, annual sessions focused on broad information sharing. The Global Stocktake (GST) also creates structured opportunities for scientific input. Every five years, it brings together Parties, experts, UN agencies, and observers to assess collective progress toward the Paris goals, identify knowledge gaps, and propose next steps.

Alongside these formal routes are numerous informal channels of influence. Side events, pavilions, exhibitions, policy briefings, research reports, and bilateral meetings with delegations all provide avenues for evidence-based engagement. Much of the day-to-day knowledge exchange around COP happens in these semi-formal and informal settings. We believe this is where the bulk of HEI activity is at most COPs and SBSTs.

The key body coordinating HEI observers is the Research and Independent Non-Governmental Organisations (RINGO) constituency – one of nine recognised observer groups under the UNFCCC. RINGO’s mandate is explicitly non-advocacy: to provide objective scientific input from academia. At COP and SB meetings, RINGO organises daily meetings to brief members, share developments, and coordinate observation at constituted body sessions. Between these meetings, it facilitates information sharing, capacity building and research collaboration on issues related to global negotiations.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the study of the process itself – analysing how the UNFCCC functions and evolves and ensuring transparency and accountability – is a vital area of expertise. Through this meta-level research, RINGO members and HEI researchers contribute significant insight into how global environmental governance operates, the implications of negotiated positions and decisions and how it might be improved.

COP28 UAE. Photo credit: Dr Kristy Faccer

3. Presidency Agenda

Track 3 focuses on the role of the COP Presidency – a central but often under-examined actor in shaping COP dynamics. The Presidency serves as an agenda setter and facilitator. It doesn’t dictate outcomes but plays a vital role in guiding discussions, building consensus, and steering negotiations toward agreement. They can also champion particular agenda items resulting in legacy agreements that bear the host city’s name, such as the Glasgow Climate Pact or Sharm El-Sheik Adaptation Agenda, whose implementation mechanisms are usually carried forward to figure out in future COPs.

Beyond the official negotiation agenda, the Presidency develops a thematic agenda designed to engage non-state actors and frame the broader public narrative around the conference.

Hosting a COP is also a significant political opportunity. For the Presidency country, it can demonstrate international leadership, attract investment and collaboration, and shape both domestic and global climate narratives. These dynamics create valuable openings for universities, particularly those with existing relationships with government.

Recent years have seen a rise in national HEI climate networks developed in response to COP Presidencies – such as the COP26 Universities Network (now the UK Universities Climate Network), the UAE Universities Climate Network for COP28, and the Azerbaijan University Climate Network (AUNCC) for COP29. Some Presidencies have also appointed academic or education liaisons to formalise engagement, such as the COP28 Presidency’s appointment of Rose Armour as Senior Advisor on Education, which provide universities with a clear channel for collaboration and input.

An engaged and well-coordinated global HEI community such as the one being fostered by higher education networks can help to support these outcomes. While the extent and nature of engagement depend heavily on the Presidency’s priorities and accessibility of focal points, groups like the Higher Education Climate Network of Networks (NoN) now provide an international platform for coordination, helping share experience between host-country institutions and those that have engaged previously.

For insight into the challenges and opportunities that Presidencies face, see Chatham House’s analysis of COP29: “Azerbaijan’s Climate Leadership Challenge”, which offers a useful case study of the political and strategic balancing act involved.

Panel COP27. Photo credit: Julia Kulik

4. Climate Action Agenda

Track 4 covers the Global Climate Action Agenda (GCAA) – more formally known as the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action (MPGCA).

This UNFCCC framework recognises, mobilises, and supports climate action by non-state actors (NSAs) such as cities, businesses, and civil society organisations. Its aim is to bridge the gap between international commitments and real-world implementation, turning pledges into progress through collaboration, accountability, and visibility.

The framework is formally recognised under the Paris Agreement, giving it a distinct but complementary role within the UNFCCC landscape – connected to, yet separate from, the negotiations themselves. The approach gained real momentum around the 2015 Paris COP, first as the Lima–Paris Action Agenda and later relaunched as the Marrakech Partnership.

The Partnership is led by the UN Climate High-Level Champions, appointed by each COP Presidency, supported by a small team and dedicated UNFCCC staff. Its philosophy is distinctly stakeholder-led: it focuses on accelerating the actions of NSAs rather than governments, on the basis that stronger ambition among these groups can, in turn, catalyse greater ambition from national governments through their NDCs. Much of this focus in recent years has been on the opportunities presented by real economy actors (e.g. financial institutions, major industry groups).

For COP30, there has been a concerted effort to align Tracks 4 and 5, bringing the Presidency and the Climate Action Agenda together under the six thematic axes and thirty objectives. Each objective is supported by an “activation group” responsible for convening partners and scaling existing initiatives.

Universities have been involved in the Partnership from its early days, largely through individual academic engagement, though their involvement as representatives of a non-state actor group or sector per se has been limited. One key channel of engagement is the Race to Zero for Universities and Colleges, which brings higher education institutions into the broader global effort to achieve net zero.

Beyond direct participation, universities play an enabling role – mobilising research, expertise, and convening power to strengthen the wider Climate Action Agenda. Much of this engagement happens through alliances and convening bodies, such as We Mean Business, which act as brokers for different stakeholder groups.

More recently, HEI networks have become increasingly active within this space – including through the Network of Networks (NoN), the Race to Zero Universities and Colleges (RtZ U&C led by EAUC and UC3), and the International Universities Climate Alliance’s (IUCA) work on building an SME-focused research community in response to a major new campaign by the Climate Champions team. Both NoN and the RtZ U&C participate in Activation Group 18, which focuses on developing accelerated solutions for “education, capacity-building, and job creation to address climate change.”

Photo credit: Dr Kristy Faccer

5. State or Government Engagement and NDCs

The fifth and final track of COP engagement isn’t really about COP itself. Its focus lies closer to home – at the national or subnational level where climate commitments are conceived, negotiated, and implemented.

The entire Paris system is state-driven, placing responsibility on national governments to chart their own routes to decarbonisation through their NDCs. NDCs are the mechanism through which Parties outline their climate actions and commitments every five years, each intended to “ratchet up” ambition compared to the last. Although NDCs are submitted to the UNFCCC, the substance is determined domestically – shaped by national policy processes, political negotiations, and institutional capacities.

Broadly speaking, universities and academic institutions can contribute in two main ways. First, through direct engagement, supporting ministries in the design, implementation, and evaluation of NDCs and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). And second, through indirect influence, engaging in national and subnational policy dialogues, providing research evidence, and shaping public understanding of climate action. In most countries, this conversation also plays out at the subnational level, where cities play a key role in climate action and where regional or local governments hold significant responsibility for energy, transport, housing, or land-use policy.

Universities often have strong relationships with the government, making them well positioned to contribute to new policy developments. In the UK, for example, academia works closely with the Climate Change Committee (CCC) – the independent statutory body that advises government and devolved administrations on carbon budgets, adaptation, and progress toward net zero. The UK’s NDC is directly informed by CCC analysis, with academics contributing through commissioned research, advisory roles, consultation submissions, and collaborative projects.

The UK also benefits from a well-established science–policy interface through the Government Chief Scientific Adviser (GCSA) network. Each government department has its own Chief Scientific Adviser (CSA) – typically a senior academic seconded into government – who helps translate research evidence into policy advice, including on climate issues.

These structures differ across countries, but the underlying principle is the same: national and subnational engagement is inseparable from international climate diplomacy. The commitments that drive the COP process originate within domestic policymaking. For universities, this means international engagement strategies must be aligned with national and local ones. Effective influence at COP begins with strong, sustained relationships and evidence-based collaboration at home.

Conclusion

Universities are increasingly visible at COPs – hosting events, joining delegations, and showcasing research – yet too often this happens without a clear understanding of the nature of each opportunity to engage and pathways to influence that they present.

As the five tracks show, each route to impact exists both within and beyond COP itself. Even the formal negotiations take place largely in advance. To gain real value, COP should be viewed not as a single event but as part of an ongoing dialogue – one moment in a continuous cycle of engagement with international, national, and sector-wide partners.

Attending COP can of course offer powerful opportunities for visibility and networking. Running an event or presenting research can help reach particular audiences and contribute to the public conversation – and that is a valid and valuable form of impact. But it’s worth asking whether COP is the most effective or efficient way to achieve that goal, given its complexity, cost (both financial and carbon), and the fact that many interactions take place within a “bubble” of familiar networks and communities. Other points in the process – pre-COP meetings, national consultations, or post-COP follow-ups – may offer more direct routes to the stakeholders who shape outcomes.

Ultimately, the message is simple: influence at COP begins long before you arrive. By understanding where decisions are made, building and contributing to coalitions for coordinated impact, and locating change efforts within these five tracks, universities can better focus their efforts, align their strategies, and play a more deliberate, effective role in contributing to and shaping global climate action.

Authors:

Stephen Davison, Director of Strategy, Cambridge Zero, University of Cambridge

Dr Kristy Faccer, Director of the President’s Advisory Committee for Environment, Climate Change and Sustainability (CECCS) at the University of Toronto